Med info

Uveitis (Iritis): Causes, Types, Symptoms, Diagnosis, and Treatment Options

What is iritis?

Iritis is an inflammation of the iris—the colored part of the eye that regulates how much light enters through the pupil. It develops when the immune system attacks eye tissues, or as a result of an infection, autoimmune disease, or direct trauma to the eye.

Iritis is considered a form of uveitis and may be confined to the anterior part of the eye or extend to involve other structures of the uveal tract, such as the ciliary body and the choroid.

This condition can lead to eye pain, redness, blurred vision, and marked sensitivity to light. If not diagnosed and treated promptly and appropriately, it can result in serious complications, including raised intraocular pressure, glaucoma, or even vision loss.

Understanding what iritis is, along with its causes and symptoms, is therefore essential for early detection and for seeking timely evaluation and management by an ophthalmologist.

Types of Uveitis

Uveitis is classified into several main types according to the location of inflammation within the eye. This classification helps establish an accurate diagnosis and guides the choice of appropriate treatment.

Anterior uveitis is the most common form. It affects the iris and the anterior part of the ciliary body, and often presents with eye redness, pain, and marked sensitivity to light (photophobia).

Intermediate uveitis involves the central vitreous region of the eye and may be associated with the appearance of floaters and blurred vision.

Posterior uveitis affects the retina and choroid at the back of the eye. It is considered one of the more serious forms because, if not treated promptly, it can lead to significant deterioration in visual acuity.

There is also panuveitis, in which inflammation involves the anterior, intermediate, and posterior segments of the eye. This is one of the most complex types and requires close, continuous follow‑up by an ophthalmology specialist.

Recognizing the different types of uveitis helps patients appreciate the importance of early diagnosis and strict adherence to treatment, in order to prevent complications such as glaucoma, cataract, or permanent loss of vision.

Anterior Uveitis

Anterior uveitis is the most common form of uveitis. It affects the front part of the eye, particularly the iris and the anterior portion of the ciliary body.

It is often associated with autoimmune diseases such as ankylosing spondylitis, psoriasis, or inflammatory bowel disease, although in some cases it can occur without an identifiable cause.

Key symptoms include eye redness, severe pain that worsens with light exposure (photophobia), blurred vision, and excessive tearing.

Early diagnosis is crucial, as untreated anterior uveitis can lead to serious complications such as ocular hypertension, glaucoma, or iris synechiae (adhesions of the iris).

Treatment usually consists of topical corticosteroid eye drops and mydriatic/cycloplegic drops to dilate the pupil, along with management of any underlying systemic disease, under the care of an ophthalmologist experienced in uveitis.

Understanding this type of uveitis highlights the potential seriousness of uveitis in general and the importance of seeking medical evaluation whenever unusual eye symptoms appear.

Posterior Uveitis

Posterior uveitis is a form of uveitis that involves the back segment of the eye, including the choroid, retina, and sometimes the optic nerve.

It is less common than anterior uveitis but tends to be more serious because it directly affects the retina, which is responsible for central vision and fine visual detail.

Posterior uveitis may be associated with systemic conditions such as toxoplasmosis, sarcoidosis, Behçet’s disease, or specific viral and bacterial infections.

Symptoms may include sudden or gradual decrease in visual acuity, the perception of floaters (moving dark spots or specks), image distortion (metamorphopsia), and sometimes mild pain or even no pain at all.

Diagnosis requires detailed ocular examination, including dilated fundus examination, retinal imaging (such as optical coherence tomography and fluorescein angiography), and may also involve blood tests and other imaging studies.

Treatment depends on the underlying cause and may include systemic corticosteroids (oral or periocular injections), immunosuppressive agents, and, when indicated, appropriate antimicrobial or antiviral therapy.

Prompt management of posterior uveitis reduces the risk of permanent vision loss and underscores the need to approach any form of uveitis within a comprehensive framework of ocular and systemic health.

Intermediate Uveitis

Intermediate uveitis is a subtype of uveitis that involves the middle segment of the eye, primarily the vitreous and the peripheral retina/pars plana region.

It is sometimes referred to as “vitritis” or “intermediate uveitis,” and, although less common than anterior uveitis, it can be associated with autoimmune diseases or multiple sclerosis.

Patients typically present with complaints of floaters or dark spots within the visual field and blurred vision, rather than pronounced eye pain or marked redness.

The condition may affect one or both eyes and is often chronic or relapsing in nature.

Diagnosis requires careful examination of the vitreous and peripheral retina, often using indirect ophthalmoscopy, together with additional investigations to look for an underlying systemic disorder.

Management may include corticosteroids in the form of eye drops, periocular or intravitreal injections, and, in more severe or persistent cases, systemic immunosuppressive or biologic therapies to control inflammation.

Recognizing intermediate uveitis as one of the distinct forms of uveitis helps clarify the spectrum of this disease and emphasizes the importance of early detection to protect retinal integrity and preserve vision.

Panuveitis (Diffuse Uveitis)

Panuveitis is the most extensive and one of the most severe forms of uveitis, involving virtually all segments of the eye—anterior, intermediate, and posterior—at the same time.

It indicates widespread intraocular inflammation and may be associated with severe autoimmune disorders, systemic infections, or complex inflammatory diseases such as Behçet’s disease or sarcoidosis.

Symptoms typically include marked eye redness, significant pain, pronounced light sensitivity, and substantial blurring or loss of vision, often accompanied by floaters and visual distortions.

Panuveitis is considered an ophthalmic emergency, as delays in treatment markedly increase the risk of permanent complications such as cataract formation, glaucoma, or irreversible damage to the retina and optic nerve.

Diagnosis requires a comprehensive ocular and systemic evaluation, including detailed fundus examination, retinal imaging (e.g., OCT), immunologic and infectious workup, and sometimes chest or whole‑body imaging.

Treatment is usually based on a combination of intensive topical and systemic corticosteroids, potent immunosuppressive medications, and, where appropriate, biologic agents, with joint follow‑up by a uveitis specialist and a rheumatologist or immunologist.

Understanding panuveitis within the broader classification of uveitis illustrates how severe this condition can be and why no warning signs involving the eyes should be ignored, particularly in patients with known autoimmune or chronic inflammatory diseases.

What causes uveitis?

The causes of uveitis are varied and involve immune‑mediated mechanisms, infections, and direct trauma to the eye, so identifying the underlying trigger is crucial for choosing the right treatment.

In many cases, uveitis is associated with autoimmune diseases such as ankylosing spondylitis, rheumatoid arthritis, and Behçet’s disease, in which the immune system mistakenly attacks ocular tissues, leading to redness, pain, and blurred vision.

Uveitis can also be triggered by viral, bacterial, or parasitic infections—such as herpes, tuberculosis, and toxoplasmosis—which provoke irritation and inflammation of the inner layers of the eye.

In some patients, the cause is direct ocular trauma, previous eye surgery, or the entry of a foreign body, all of which can elicit an intense inflammatory response.

In a subset of cases, no clear cause can be identified and the condition is labeled idiopathic uveitis. Because of this, anyone who develops symptoms like eye pain, light sensitivity, or blurred vision should see an ophthalmologist promptly for early diagnosis and prevention of complications.

Immune‑mediated causes

Immune‑mediated mechanisms are among the most common triggers of uveitis. In these conditions, the immune system mistakenly targets ocular tissues as if they were foreign bodies.

This abnormal response leads to inflammation within the iris and the anterior or posterior segments of the eye, resulting in redness, pain, and blurred vision.

Such immune dysregulation is often associated with systemic autoimmune diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and ankylosing spondylitis. For this reason, diagnosing uveitis usually requires a comprehensive assessment of the patient’s overall health.

Understanding the immune‑mediated causes of uveitis is essential for selecting appropriate therapy—such as corticosteroids and immunosuppressive agents—and for limiting the complications of chronic ocular inflammation.

Bacterial and viral infections

Bacterial and viral infections are key contributors to uveitis. Microorganisms can reach the eye via the bloodstream or spread from a nearby local infection.

Common bacterial causes include *Mycobacterium tuberculosis* (tuberculosis), *Brucella* species (brucellosis), and certain sexually transmitted infections. Frequent viral culprits include herpes simplex virus (HSV), varicella‑zoster virus (VZV), and cytomegalovirus (CMV).

These pathogens induce direct inflammation of the iris and other intraocular structures, leading to symptoms such as marked photophobia, visual haze, and ocular pain.

Identifying whether the uveitis is of bacterial or viral origin is crucial for guiding targeted treatment with antibiotics or antiviral medications, preventing recurrences, and avoiding permanent ocular damage.

Direct ocular trauma

Uveitis may also arise following direct trauma to the eye, such as blunt injuries, accidents, or penetration by a sharp or foreign object.

Such incidents can damage intraocular tissues, including the iris, and trigger a defensive inflammatory response.

In some cases, uveitis develops after ocular surgery if there is significant postoperative irritation or secondary infection, making meticulous postoperative care essential to minimize complications.

Prompt management of eye injuries and timely specialist ophthalmic evaluation help reduce the risk of chronic uveitis and preserve visual function.

Chronic diseases associated with uveitis

A number of chronic systemic diseases are associated with an increased risk of uveitis, which may present as one of the ocular manifestations of a broader systemic disorder.

Prominent examples include Behçet’s disease, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, sarcoidosis, and various rheumatologic conditions.

In these settings, uveitis is not merely a localized eye problem but part of a generalized inflammatory process, necessitating coordinated care between the ophthalmologist and internists or rheumatologists.

Optimal control and early treatment of the underlying chronic disease help reduce the frequency of uveitis flares and limit serious complications such as cataract, glaucoma, and progressive vision loss.

Symptoms of Uveitis

Uveitis symptoms usually appear suddenly and may affect one eye or both. They include pronounced eye redness, a deep aching pain that worsens with light exposure (photophobia), blurred or hazy vision, as well as the perception of floating dark spots (floaters) or flashes of light within the visual field.

Patients may also experience excessive tearing, a sensation of heaviness or discomfort inside the eye, and difficulty focusing while reading or using digital screens.

In acute uveitis, visual acuity can decline noticeably and vision becomes clearly blurred, whereas chronic uveitis may progress silently with subtler symptoms, yet it carries a higher risk of long‑term damage.

Any sudden change in vision or onset of eye pain should never be ignored, as untreated uveitis can lead to serious complications such as glaucoma, cataracts, or permanent vision loss. Prompt evaluation by an ophthalmologist at the first sign of symptoms is therefore essential.

Eye Pain

Eye pain is one of the most common symptoms of uveitis. Patients often describe it as a stabbing sensation or a deep, throbbing pressure in or around the eye.

The pain may worsen with eye movement or exposure to light, and it can be constant or intermittent depending on the severity and underlying cause of the uveitis.

Many people initially dismiss eye pain as simple eye strain or fatigue. However, persistent pain accompanied by other symptoms such as eye redness or blurred vision requires prompt evaluation by an ophthalmologist.

Early diagnosis of eye pain related to uveitis is crucial to protect vision and prevent serious complications that may affect the retina or optic nerve.

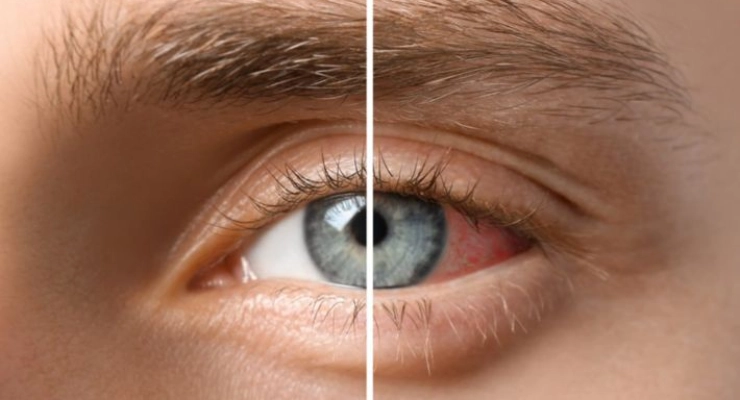

Eye Redness

Eye redness is a clear and common sign of uveitis. It often appears in a ring around the cornea or may be more diffusely spread, resulting from dilation of blood vessels in the inflamed eye.

Redness may be accompanied by a burning sensation, the feeling of a foreign body in the eye, excessive tearing, and marked light sensitivity.

Not every red eye is due to uveitis; however, when redness occurs together with eye pain and blurred vision, intraocular inflammation should be suspected rather than a simple superficial condition such as conjunctivitis.

Recognizing the specific pattern of eye redness early on helps direct the patient quickly to an eye specialist to confirm the diagnosis of uveitis and start appropriate treatment before permanent complications develop.

Blurred or Reduced Vision

Blurred or reduced vision is one of the most serious symptoms of uveitis, as it indicates involvement of intraocular structures responsible for image clarity and visual quality.

Patients may notice a veil or haze in front of the eye, difficulty reading, the presence of floaters and dark spots, or a general reduction in visual acuity.

Visual blurring in uveitis can result from accumulation of inflammatory cells in the vitreous humor, on the corneal surface or lens, or from involvement of the retina and changes in intraocular pressure.

Ignoring decreased vision caused by uveitis can lead to permanent visual loss if not treated in a timely manner, so any change in visual clarity should prompt immediate consultation with an ophthalmologist.

Marked Light Sensitivity (Photophobia)

Severe sensitivity to light, known medically as photophobia, is a hallmark symptom of uveitis. The patient experiences pain or intense discomfort when exposed to sunlight or bright indoor lighting.

This sensitivity may cause the person to keep their eyes partially closed or to wear sunglasses even indoors, due to pricking eye pain or headache triggered by light exposure.

Photophobia results from irritation of the iris and inflammation of the internal eye tissues, making the eye’s response to light much more intense than normal.

When photophobia occurs together with eye redness, eye pain, and blurred vision, uveitis becomes a likely diagnosis and urgent medical assessment is needed to protect the eye and relieve symptoms.

Eye-Related Headache

Headache associated with eye disease is a common feature of uveitis. It typically affects the forehead, the area around the eyebrows, or the region surrounding the affected eye.

This type of headache often worsens with visual tasks that require focus, exposure to light, or prolonged screen use, and may occur alongside eye pain and redness.

In uveitis, the headache arises from constant strain on the eye muscles and ongoing intraocular inflammation, and in some cases may signal increased intraocular pressure or extension of inflammation to other ocular structures.

When recurrent headache is accompanied by eye symptoms such as blurred vision and light sensitivity, relying solely on painkillers is not sufficient; an ophthalmologic evaluation is necessary to rule out or confirm uveitis and begin early treatment.

When Is Uveitis Considered Serious?

Uveitis becomes serious when it is left untreated or keeps recurring, as it can lead to long-term complications such as elevated intraocular pressure (glaucoma), cataract formation, macular or retinal edema, and even partial or complete loss of vision.

The risk increases when uveitis is accompanied by severe eye pain, sudden blurred or hazy vision, the appearance of floaters, marked light sensitivity (photophobia), or pronounced redness that does not improve over a few days.

Uveitis is also particularly concerning when it is associated with systemic autoimmune or chronic inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, Behçet’s disease, or viral and bacterial infections affecting the body.

In such cases, the patient requires a thorough assessment by an ophthalmologist, including detailed investigations and prompt initiation of appropriate therapy to control the inflammation, protect the optic nerve and retina, and reduce the likelihood of permanent ocular damage and irreversible vision loss.

How Is Uveitis Diagnosed?

Diagnosing uveitis starts with taking a detailed medical history, including how long symptoms have been present—such as eye redness, pain, blurred vision, and light sensitivity—as well as asking about any autoimmune diseases or previous inflammatory conditions elsewhere in the body.

The ophthalmologist then performs a comprehensive eye examination using a slit lamp to carefully assess the iris, cornea, and anterior chamber of the eye, looking for signs of inflammation such as inflammatory cells and haziness (flare) inside the eye.

Intraocular pressure is often measured to rule out complications like ocular hypertension or secondary glaucoma related to uveitis. The back of the eye (fundus) is also examined after dilating the pupil to check the retina and optic nerve.

In some cases, the doctor may request blood tests, immunological workup, or imaging studies (such as X‑ray or MRI) to look for an underlying systemic cause of uveitis, including autoimmune diseases or chronic infections.

Accurate and early diagnosis of uveitis is crucial for selecting the appropriate treatment and reducing the risk of long‑term complications that can impair visual acuity.

Slit-Lamp Examination

The slit-lamp examination is the cornerstone for accurately diagnosing uveitis.

The ophthalmologist uses a specialized device called a slit lamp, which is a biomicroscope equipped with a focused beam of light that allows detailed visualization of the anterior and posterior segments of the eye.

During the examination, the doctor assesses the iris, cornea, anterior chamber, and lens, and may extend the evaluation to the vitreous and retina to detect any signs of anterior, intermediate, or posterior uveitis.

This exam helps identify inflammatory cells, keratic precipitates on the cornea, posterior synechiae of the iris, and vitreous opacities—key signs for determining the type and severity of uveitis.

The high diagnostic accuracy of slit-lamp examination makes it a pivotal tool in planning uveitis management and selecting the appropriate eye drops or systemic medications.

Intraocular Pressure Measurement

Measuring intraocular pressure (IOP) is an important step in the work‑up and follow‑up of uveitis.

The ophthalmologist uses a tonometer to determine whether uveitis has led to abnormally elevated or reduced eye pressure.

Intraocular inflammation can impede aqueous humor outflow or alter its production, potentially resulting in serious complications such as glaucoma or optic nerve damage if not detected early.

Regular monitoring of IOP during uveitis treatment helps assess the response to corticosteroids or other topical therapies and ensures that these medications are not causing a harmful rise in eye pressure.

For this reason, IOP measurement is considered an integral part of the diagnostic and follow‑up protocol for uveitis to preserve long‑term visual function.

Additional Tests to Identify the Underlying Cause

In many cases, the clinician will not rely on clinical examination alone, but will order additional tests to more precisely identify the cause of uveitis.

These may include fundus photography, fluorescein angiography, and optical coherence tomography (OCT), which help assess the retina and optic nerve and detect any edema or exudation related to inflammation.

Computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may also be requested if there is suspicion of systemic disease or deep‑seated inflammatory processes involving the eye.

These ancillary investigations help distinguish between infectious uveitis, autoimmune or inflammatory causes, trauma‑related inflammation, and intraocular tumors, thereby directing treatment toward the underlying pathology rather than just alleviating symptoms.

The more precise the etiologic diagnosis of uveitis, the greater the likelihood of controlling inflammation and preventing recurrences or progression to chronic complications.

When Are General Laboratory Tests Ordered?

An ophthalmologist will typically request systemic laboratory tests when there is suspicion that uveitis is associated with a systemic disease or an underlying immune disorder.

These tests often include complete blood count, liver and kidney function tests, autoimmune panels, and assays to detect bacterial, viral, or parasitic infections that may trigger uveitis.

The physician may also order specific tests such as rheumatoid factor, inflammatory markers (CRP and ESR), and screening for tuberculosis, syphilis, or toxoplasmosis, depending on associated symptoms and the patient’s medical history.

The aim of these general tests is to link uveitis to any systemic condition—such as rheumatic diseases, inflammatory bowel disease, or autoimmune disorders—and to formulate a comprehensive treatment plan that addresses both the eye and the rest of the body.

Ordering systemic laboratory investigations in the context of uveitis is essential in recurrent, severe, or idiopathic cases to ensure safe, effective therapy and to reduce the risk of future relapses.

Treatment Options for Uveitis

Management of uveitis depends on the severity of inflammation and its underlying cause, with the primary goals being pain control, preserving vision, and preventing permanent ocular damage.

Ophthalmologists typically start with topical corticosteroid eye drops to reduce inflammation, along with pupil-dilating (mydriatic) drops. These dilating drops help relieve pain caused by ciliary muscle spasm and prevent adhesions between the iris and the lens (posterior synechiae).

In more severe or chronic cases, systemic corticosteroids may be prescribed either orally or via periocular injections. When uveitis is associated with autoimmune conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis or ulcerative colitis, immunosuppressive or immunomodulatory agents may be required to control the underlying disease and reduce recurrence.

If a bacterial or viral infection is identified as the cause, appropriate antibiotics or antiviral medications are used under close medical supervision to target the specific pathogen.

Early diagnosis, regular follow‑up, and strict adherence to the treatment plan are crucial, as neglecting uveitis can lead to serious complications such as cataracts, elevated intraocular pressure (glaucoma), or irreversible loss of visual acuity.

Therapeutic eye drops

Therapeutic eye drops are the first line of treatment for uveitis. They help relieve pain and control intraocular inflammation.

These usually include corticosteroid eye drops to reduce inflammation, along with mydriatic (pupil-dilating) drops to prevent adhesions between the iris and the lens (posterior synechiae) and to ease painful ciliary muscle spasms.

The ophthalmologist tailors the type of drops, their frequency, and duration of use according to the type and severity of uveitis, and it is essential to follow the prescribed regimen precisely and avoid stopping the drops abruptly to prevent relapse or complications.

When used correctly, therapeutic eye drops can rapidly control uveitis, maintain clear vision, and help prevent long‑term complications such as glaucoma or cataract.

Anti‑inflammatory medications

Anti‑inflammatory drugs are a cornerstone of uveitis management, especially in moderate to severe cases or when the eye does not respond adequately to topical therapy alone.

This category includes corticosteroids taken orally, injected periocularly (around the eye), or intravitreally (inside the eye), in addition to non‑steroidal anti‑inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in selected cases.

Careful dose adjustment and close follow‑up with the ophthalmologist and internist help minimize side effects such as elevated intraocular pressure or systemic adverse effects of steroids.

Choosing the appropriate anti‑inflammatory agent is a key component of the overall treatment strategy, aiming to suppress inflammatory activity, protect delicate ocular tissues, and preserve visual function over the long term.

Immunomodulatory therapy for chronic cases

In chronic or recurrent uveitis, or when the inflammation is associated with autoimmune diseases such as inflammatory arthritis or inflammatory bowel disease, long‑term immunomodulatory therapy may be required.

This includes drugs that suppress or modulate immune system activity, such as methotrexate or biologic agents, with the goal of controlling inflammation at its source and reducing dependence on corticosteroids.

Immunomodulatory treatment requires close monitoring and regular blood tests and organ function assessments to ensure patient safety and limit potential complications.

This form of therapy is considered an advanced step in managing chronic uveitis, as it helps reduce the frequency of flare‑ups, protects the retina and optic nerve, and improves long‑term quality of life.

Treating the underlying cause, when present

Long‑term success in managing uveitis depends on identifying and treating the underlying cause, when present, since uveitis may be a manifestation of a deeper systemic problem.

It can be associated with autoimmune diseases, bacterial or viral infections, rheumatologic disorders, or even gastrointestinal or respiratory conditions.

For this reason, the ophthalmologist often collaborates with other specialists to perform the necessary laboratory and imaging studies—such as blood tests and radiologic scans—to reach an accurate diagnosis.

By treating the underlying cause through appropriate pharmacologic therapy, lifestyle modification, or targeted treatment of a specific infection, the risk of uveitis recurrence decreases, the eye’s response to topical and systemic therapies improves, and the chances of preserving vision and preventing future complications are significantly enhanced.

How long does it take to treat uveitis?

The duration of uveitis treatment varies from one patient to another, depending on the underlying cause, the severity of inflammation, and how well the eye responds to medication.

Acute anterior uveitis often responds to treatment with topical corticosteroid eye drops and mydriatic (pupil‑dilating) drops within about 2–6 weeks. During this period, regular follow‑up with an ophthalmologist is essential to taper the steroid dose gradually and reduce the risk of relapse.

In chronic uveitis, or when the inflammation is associated with autoimmune diseases, treatment may last for several months and can require systemic immunosuppressive agents or oral corticosteroids for longer periods under specialist supervision.

Early initiation of treatment is critical, and medications should never be stopped abruptly without medical advice. Neglecting treatment or discontinuing it suddenly can prolong recovery and increase the risk of complications such as ocular hypertension, glaucoma, or macular and retinal damage.

Ultimately, the exact duration of uveitis treatment depends on accurate diagnosis, adherence to the prescribed regimen, and regular monitoring to assess disease activity and adjust the treatment course safely.

Can Uveitis Be Prevented?

While complete prevention of uveitis is not always possible—especially when it is associated with autoimmune or systemic conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis or Behçet’s disease—there are several measures that can significantly reduce the risk of developing it or experiencing recurrent flare‑ups.

Good control of chronic underlying diseases, along with regular follow‑up with both an ophthalmologist and an internist or rheumatologist, plays a key role in the early detection of any inflammatory changes in the uvea and in initiating treatment before the condition progresses.

It is also advisable to protect the eyes from trauma by wearing safety goggles in hazardous work environments, and to avoid unprotected exposure to intense ultraviolet (UV) radiation by using high‑quality, reliable sunglasses.

Infection prevention can also help lower the risk of infectious uveitis. This includes proper hand hygiene, avoiding the sharing of eye products or contact lenses, and strictly adhering to contact lens cleaning and disinfection instructions to reduce the likelihood of bacterial or viral eye infections.

If symptoms such as eye pain, sudden redness, blurred vision, or decreased visual acuity occur, an urgent evaluation by an ophthalmologist is essential. Early diagnosis and prompt treatment remain the most effective strategies for preventing serious complications of uveitis.

The Difference Between Uveitis and Other Eye Inflammations

Uveitis differs from more common eye inflammations such as conjunctivitis or keratitis in several key aspects related to the site of inflammation, symptom severity, and risk of complications.

In uveitis, the inflammation affects the uveal tract—the middle layer of the eye responsible for regulating the amount of light entering the eye (including the iris, ciliary body, and choroid). This typically causes deep ocular pain, blurred vision, marked sensitivity to light (photophobia), and may be accompanied by floaters—small dark spots moving across the field of vision.

By contrast, other eye infections such as conjunctivitis usually present with superficial redness, discharge, and itching, and in most cases do not significantly affect vision.

Uveitis is also more likely to be associated with systemic autoimmune diseases or generalized infections, which makes it a more complex condition that requires accurate diagnosis and specialized management to prevent serious complications such as ocular hypertension (raised intraocular pressure), cataracts, or even permanent vision loss. This is unlike many minor eye inflammations that often resolve with short-term topical therapy.

Recognizing the distinction between uveitis and other types of eye inflammation enables patients to seek prompt medical attention and avoid neglecting serious symptoms that could threaten their vision.

Uveitis vs. Conjunctivitis

Uveitis is fundamentally different from conjunctivitis, even though both fall under the umbrella of eye inflammation.

In uveitis, the inflammation affects the uveal tract (the middle layer of the eye), which includes the iris. This can lead to deep, internal eye pain, blurred vision, marked sensitivity to light (photophobia), and the appearance of floaters in the visual field.

Conjunctivitis (commonly known as “pink eye”) is an inflammation of the thin, transparent membrane (conjunctiva) that covers the white of the eye and lines the inside of the eyelids. It typically presents with obvious redness, watery or purulent discharge, and a sensation of itching or burning, but without deep eye pain or a sudden, significant drop in visual acuity.

Distinguishing uveitis from conjunctivitis is crucial, because uveitis may be associated with autoimmune diseases or systemic inflammatory conditions and often requires prompt treatment with corticosteroids or immunosuppressive agents to preserve vision. Conjunctivitis, on the other hand, is most often caused by viral or bacterial infections or allergies and is usually managed with simple topical eye drops.

Understanding the difference between uveitis and more superficial eye inflammations such as conjunctivitis helps patients seek urgent medical evaluation when worrying symptoms appear, thereby reducing the risk of vision-threatening complications.

Uveitis vs. Keratitis

Uveitis differs from keratitis in the location of inflammation, its implications, and treatment strategies, even though both conditions may share some symptoms like eye redness and pain.

In uveitis, the inflammation occurs inside the eye, involving the iris and other parts of the uveal tract. This results in internal eye pain, blurred vision, photophobia, and sometimes headache on the same side as the affected eye.

Keratitis, however, is an inflammation of the cornea—the clear, dome-shaped front surface of the eye that plays a major role in focusing light. It typically presents with severe pain, a foreign-body sensation, excessive tearing, blurred or significantly reduced vision, and may be accompanied by corneal ulcers, particularly in bacterial or viral infections such as herpes simplex keratitis.

Both uveitis and keratitis are considered ocular emergencies, but their management differs. Uveitis usually requires corticosteroid eye drops and mydriatic/cycloplegic drops under the supervision of an ophthalmologist. In contrast, infectious keratitis can worsen with corticosteroids and instead requires intensive topical antimicrobial or antiviral therapy, and in some cases, systemic treatment.

Accurate clinical differentiation between uveitis and keratitis is essential to protect both the cornea and the uveal tract from permanent damage and to prevent vision loss resulting from delayed diagnosis or inappropriate management of these serious ocular inflammations.

When should you see an ophthalmologist?

You should see an ophthalmologist immediately if you notice sudden eye redness accompanied by pain, a stinging or foreign-body sensation, a feeling of pressure inside the eye, or a sudden onset of blurred vision, floaters (black spots moving in the field of vision), or flashes of light, as these may be signs of uveitis.

Emergency medical attention is also required if eye inflammation is associated with severe headache, marked sensitivity to light (photophobia), pain when looking at light, or a noticeable drop in visual acuity. Neglecting uveitis can lead to serious complications such as elevated intraocular pressure, glaucoma, cataract, and in some cases permanent vision loss.

It is also advisable to regularly follow up with an ophthalmologist if you have recurrent episodes of uveitis, or if you suffer from autoimmune diseases or chronic systemic inflammatory conditions. Early detection and accurate diagnosis are key to controlling the disease promptly, protecting the retina and optic nerve, and preserving good vision over the long term.

Book Your Medical Consultation for Uveitis Treatment at Batal Specialized Medical Complex

Batal Specialized Medical Complex provides comprehensive services for the diagnosis and treatment of uveitis, under the supervision of highly experienced ophthalmology consultants specialized in iris disorders and intraocular inflammation.

By booking an early medical consultation, you can receive an accurate assessment of your uveitis, including a thorough fundus examination, intraocular pressure measurement, and evaluation of potential underlying causes such as autoimmune diseases, infections, or trauma.

The medical team at Batal Specialized Medical Complex follows the latest evidence‑based treatment protocols, both topical and systemic, including corticosteroid eye drops, mydriatic/cycloplegic drops, and immunomodulatory therapy when indicated, with the aim of rapidly controlling inflammation and protecting the optic nerve and retina from complications.

Schedule your appointment now for uveitis treatment at Batal Specialized Medical Complex and benefit from specialized eye care and a personalized treatment plan tailored to your condition, ensuring the best possible chance of preserving visual acuity and long‑term ocular health.

Patient Guide: Frequently Asked Questions About Iritis

Can iritis be cured?

Yes, iritis can be successfully treated in most cases, especially when it is diagnosed early and the prescribed treatment plan is followed carefully. Recovery depends on the underlying cause and the type of inflammation. Mild cases often respond well to anti-inflammatory eye drops, while chronic or recurrent cases may require long-term follow-up to prevent complications and preserve vision.

Is iritis an autoimmune disease?

In some cases, yes. Iritis may be associated with autoimmune disorders, in which the immune system mistakenly attacks the tissues of the eye. It can also occur as a result of infection, eye injury, or without a clearly identifiable cause. For this reason, an ophthalmologist may request additional tests to determine whether the inflammation is related to an underlying autoimmune condition that requires specialized treatment.

Is iritis dangerous if left untreated?

Iritis can become serious if left untreated. Delayed or inadequate treatment may lead to complications such as increased intraocular pressure, cataract formation, or permanent vision impairment. Prompt evaluation by an ophthalmologist is strongly recommended as soon as symptoms appear.

How long does iritis treatment take?

The duration of treatment varies depending on the severity and cause of the inflammation. Mild cases may resolve within a few weeks, while chronic cases can take several months and require gradual treatment and close medical supervision.

Can iritis recur?

Yes, iritis can recur, particularly when it is associated with autoimmune diseases or other chronic conditions. Regular follow-up and strict adherence to medical advice play an important role in reducing the risk of recurrence and managing the condition effectively.